Market Mayhem (02/04/22)

Bonds and Yield Curves, the continued Oil Dilemma, and Putin's Ultimatum.

Dear Reader,

I hope you are well. From next week onwards, I will add a small bullet-point section to the end of the Market Mayhem posts that covers other, less significant events in markets (stock splits, M&A, disastrous or incredible earnings, among others). I hope that this will be useful to you.

Have a nice weekend.

Kind regards,

JL

Bond Market Rout and the Yield Curve

Bond market investors have not done well this quarter. Indeed, the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate index, which tracks investment grade, dollar-denominated fixed rate bonds, is down 6.2% in Q1 22. That quarterly performance is the worst for U.S. bonds since 1980, when the index lost 8.7% in Q1, and 6.6% in Q2.

The reason for this is obviously rising central bank rates, which incentivise investors to sell off bonds now in an attempt to lock in higher rates in the near future. Know that bond prices are inversely related to yields.

But the phenomenon that has received the most attention is the flat yield curve. Personally, I have a general disinterest in bonds (I think they are boring), but it has not escaped me that the yield curve is a reliable predictor of recessions, and so I will attempt to explain it here.

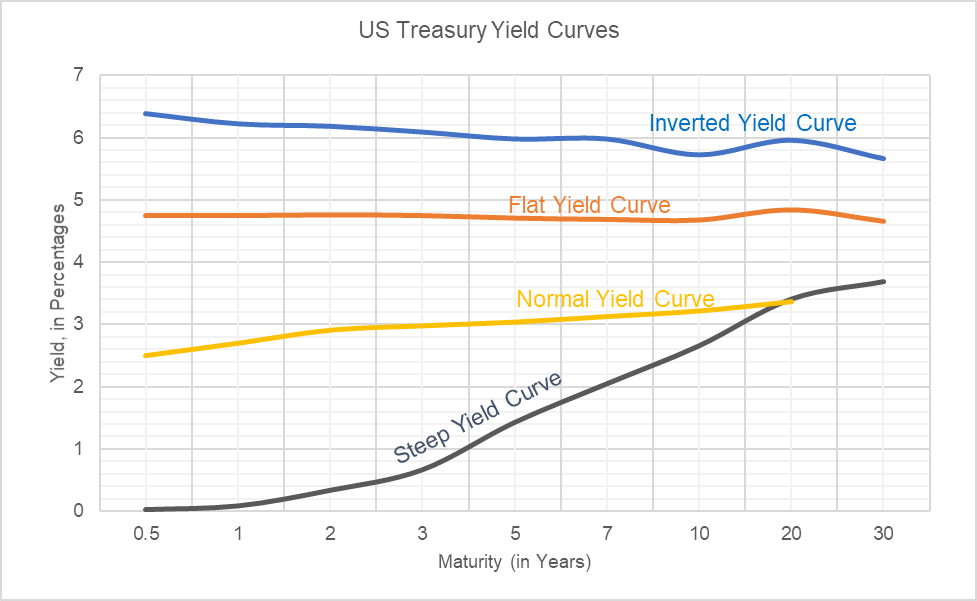

The yield curve is simply a line that plots the interest rates of two or more bonds (normally U.S. Treasurys) with identical credit ratings but different maturities.

Under normal circumstances, the yield curve has an upward slope i.e., shorter-term bonds pay lower rates than long-term bonds. This makes sense; if investors lock away their capital for 10 or 20 years, other, more attractive investment opportunities could present themselves and they expect to be compensated for this. The upward-sloping yield curve is associated with economic expansions.

But yield curve may also become inverted and show a downward slope i.e., shorter-erm bonds pay higher rates than longer-term bonds. This curve is quite a reliable predictor of economic recessions. If investors expect the economic climate to deteriorate in the near future, they will avoid and sell-off shorter-term bonds, and instead purchase longer-term bonds, so shorter-term yields rise above longer-term yields.

Below, you can see that - most of the time - a recession (shaded) followed whenever the 3-month T-Bill yield exceeded that of the 10-year T-Bond rate i.e., when the spread (difference) between the 10-Yr and 3-Month debt securities fell below zero percent.

Now, we have a transitional, flat yield curve (green), which is a marked change from the upward-sloping curve that could be seen a year ago (orange). Both Wall Street and institutions like the Fed are rightfully worried that it could invert soon, signalling a likely recession.

As with most things in finance, there are no clear cause-and-effect relationships. Some will say that the fuss about the yield curve is overblown, whilst others have a near-religious adherence to this graph. The entire concept is also a bit more complicated than explained here.

Economies are also cyclical, so even if the yield curve does invert, this may signal the beginning of a downturn, although the actual contraction may come months and years later. There is also no clear correlation between the inverted yield curve and stock market returns, and needless to say, timing the market is almost always a foolish endeavour.

The Continued Oil Dilemma

The U.S. has announced that it will release 180 million barrels of oil from its strategic petroleum reserve (SPR) over the next 6 months to reduce fuel prices, which equates to about 1/3 of its total stockpile.

Biden also stated that he would invoke the Defense Production Act - a national security mobilisation law - to boost domestic production of minerals used in clean energy technology, and called on Congress to pass a law that would accelerate the production of oil companies that have leases on federal land. Biden said that the SPR release would act as a “wartime bridge” until oil production approached demand later in the year.

There is debate about whether the release from the SPR is wise or not. Indeed, some argue that the move is a short-term fix that does not replace Russian oil in the market. It can also be conceptualised as a loan, since the SPR must eventually be refilled. Biden said that the government would be able to complete this restock at lower prices once production increases due to his other measures, but refilling the SPR could actually drive the price of oil up again.

The other problem is that the International Energy Agency (IEA) requires its members to have a minimum of 90-days worth of oil reserves, and the U.S. will barely exceed this threshold after the SPR release is complete. In other words, it will have fired its only shot, and there is always the chance that another emergency materialises that the U.S. would then have to face with depleted reserves.

“Russia is a problem that is too big for the SPR to solve. Gasoline prices are mainly influenced by crude oil prices. And crude oil prices are going to go higher as long as the Russia risk remains and intensifies.”

- Bob McNally, Analyst at Rapidan Energy Group

To me, the move seems political above all else. An announcement of a ‘massive’ and ‘unprecedented’ SPR release will naturally make voters think that Biden is actively trying to reduce their expenses at the gas pump - expenses that have risen from a national average of $2.9 to $4.2 year-over-year.

As always, there is a stalwart entity that will benefit from rising oil prices, namely the Organization for Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). The price-fixing cartel accounts for 40% of global oil production, and the U.S. has repeatedly requested that it boost production and cut its market alliance with Russia. Neither is likely to happen.

OPEC has argued that increasing production could drive higher prices, as could be seen in the price-spike 2008. Then, buyers worried that OPEC’s increased production reduced the organisations free capacity, and in turn hampered its ability to alleviate future shortages.

So, OPEC is set to stick with its modest production increases of 423,000 barrels per day, although its spare capacity equates to circa 4.2 million barrels a day, according to the IEA. And so, whatever the official reason, all parties involved know that OPEC will leverage its position for its own benefit.

Putin’s Gas Ultimatum

Putin has issued a presidential decree that will halt exports of gas to countries which have imposed sanctions on Russia… unless they make their payments in Rubles. Compliance will be tested next month, when payments for April deliveries come due.

However, the EU has remained defiant. The finance ministers of Germany and France stated that payments would continue in euros and dollars as specified in the contracts, and that they were making preparations for all scenarios. Germany is more dependent on Russian gas than France, with about 60% of its imports coming from Russia as opposed to 20% for the latter. Other countries in Europe, like Austria, Finland, and Lithuania, are at an even higher risk of economic fallout.

We can assume that Putin wants to stabilise the Ruble with this move, but it can be construed as a time-limited gamble. To illustrate, the EU is planning to cut 2/3 of Russian gas imports this year alone, and Germany - which is a prime example of naïve energy dependence - wants to end imports entirely by mid-2024.

In effect, Putin’s most important leverage is crumbling with each passing week, and it is clear that Europe will recover in the medium-term, even if there is a drastic halt of Russian gas exports. It will be painful and costly, but Russia stands to lose more, as the substantial and consistent cash flows from Europe will suddenly end. That means less resources for his conquest of Ukraine, which appears to have stalled. Hurting the other side more than your own has been the principle of economic sanctions all along.