The following stock has become quite popular among the Substack crowd, but I remain on the fence as to its prospects. This shorter discussion post is intended as an invitation to readers to share their thoughts.

Laurent-Perrier (LP) is one of three, family-owned (65%; Nonancourt) and publicly-traded champagne producers. It owns five champagne houses positioned across the upper-middle to ultra-high-end quality range: LP, Salon, Delamotte, and Champagne de Castellane. In FY23, the firm sold 11.7m bottles at an average price of €26, though one can imagine the actual price range is extremely broad, from perhaps €10 to €1500 for exclusive vintages and prestige cuvées. 87% of LP’s revenue originates from exports to big markets like the EU, USA, UK and Japan, with 13% from France (the largest single market for the stuff).

Champagne, due to its economic value to France, is strictly regulated by the Comité Champagne (CIVC), insulating producers from competition. In short, it must be produced in the Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC), a designated area of 34,200 hectares east of Paris which envelops 3 regions, 5 departments, 370 champagne houses, 16,200 winegrowers, 130 cooperatives, and more than 300 crus, or wine villages. Moreover, champagne production consists of 25 stages, and the quality of grapes used must exceed an 80% rating, after which they are categorised as either cru, premier cru, or grand cru. The defining element of production is a double fermentation: first in the vat, then in the bottle itself.

Champagne is considered non-vintage if it is aged at least 15 months, and vintage if aged more than 36 months from the bottling date. Grapes are the critical input, and comprise 3/4 of the cost of goods. About 1.2kg are required to make a standard 750ml bottle of champagne, with a typical cost per kg of €5.

LP produces 10% of its own grapes, which is below the 20% average of houses. It also uses a higher quality of grapes, with a rating of 91% compared to an 88% average. LP has 1,200 suppliers, with whom it has staggered contract renewal dates. Its brands are sold through different distribution channels or in different price ranges, ensuring they do not cannibalise each other.

As in other luxurious product categories, margins are relatively high, and houses like LP, Mumm, Möet & Chandon, Veuve Clicquot, etc., tend to focus on pricing discipline and generating brand power instead of raw volume. Other crucial actors in the champagne operation are growers, who own 90% of vineyards, and cooperatives. These sometimes produce their own product, but they reap a small fraction of the rewards, in part because they lack the brand power of houses.

As to the market, champagne’s annual TAM stands at around €6bn, with about 300m bottles shipped. Volumes have increased since the end of the last century and throughout the 2000s but have stagnated since then, whilst typical prices have constantly risen by an average of about 150 bps annually, from €10.1 in 1998 to €19.4 today, as one would expect from a protected (cartel?) network of producers.

Of the 325m bottles shipped in CY22, 42.5% went to France, 19.0% to the EU, and 38.5% to other important markets, like the US, UK, and Japan. Houses reap most of the rewards of export, as shown by their disproportionately higher share of value relative to volume, and though Non-vintage Brut is the most popular type of champagne by volume, Prestige Cuvées seem to be driving the best margins.

LP has a four-pronged strategy:

Single business: production and sale of premium champagnes exclusively.

High-quality inputs through a partnership approach with grape growers.

Portfolio of complementary brands that do not cannibalise each other.

Active control of worldwide distribution.

Execution on the first pillar has the greatest impact on revenue and margin growth. So far, performance has been quite good, with an increase in the percentage of sales from premium champagnes like the Cuvée Rosé and Grand Siècle of 34% in 2H10 to 46% in 1H24. Further execution of the premiumisation strategy and an increase in the share of higher-value exports will undoubtedly be the biggest determinants of LP’s future performance.

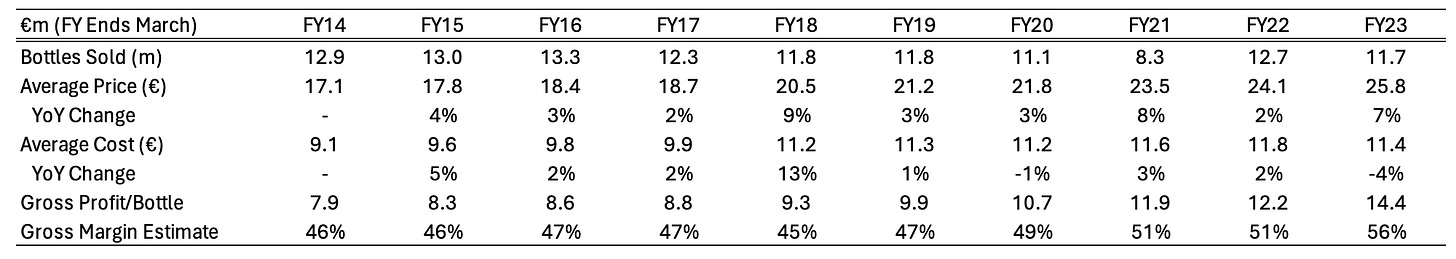

But there are several problems to consider. First, though LP’s recent performance has been very good, we have no clue as to whether this can go on and what the drivers are without speaking to management; the disclosure on this is terrible. All we know is that there was a pandemic boom and that luxury generally is decelerating. It is perfectly possible, for example, that LP’s recent success is due to an inflation mismatch, where pre-inflation costs are matched to post-inflation wholesale prices, due to the aging requirement of at least 15-months. The effect would be increasing unit profitability artificially, even if weighted average cost is used instead of FIFO alone. With a fully inventory turn every 4-years, it would also introduce the risk of margins falling off a cliff down the line.

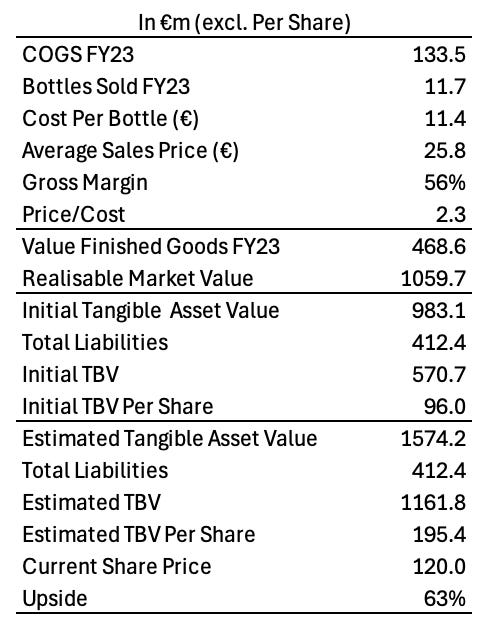

Of course, this uncertainty influences our valuation. Reluctant to build a growth forecast, I instead value LP with a status quo on average figures in the past 5-years excluding COVID (FY21). This is definitely reasonable since the firm has not truly grown in more than a decade. This method produces a ridiculous value of €17 per share. Even with very optimistic FY23 numbers, the estimate increases minimally to €38 per share.

But what about the asset side? On tangible book value per share, LP is worth at least €96, and certainly much more, if we consider that the bottles in its cellar are valued at the weighted average unit cost excluding financial expense and the prime real estate is valued at book. But how much more?

With FY23 COGS and the number of bottles sold (11.7m), we can approximate the average cost per bottle (€11.4), and from champagne revenue we know the average wholesale price (€25.8), which indicates a unit profitability of 56%. More importantly, we now also know that the price/cost factor is around 2.3, which we can use as a multiplier on the book value of finished goods (€468.6m) to estimate the market value upon sale (€1059.7m). Now, we have an adjusted TBV per share of €195 relative to a current share price of €120, and this still excludes the valuable real estate.

Of course, this calculation is somewhat flawed. For example, we can assume that a good proportion of the bottles in LP’s cellars still need to age before the true market value can be realised, and we have no insight into product mix e.g., what proportion is non-vintage, and therefore has to age for no more than 15 months at most? Besides, if LP is an asset play first and foremost, but there is no prospect of value realisation (like a treasure chest with no key), why buy it?

The second problem lies in LP’s cash flow and capital returns. Specifically, LP’s cash flow is tied up in stock expansion, with guaranteed yearly outflows and big working capital movements. Accruals profitability is all well and good, but if this does not translate into cash, and ideally sooner rather than later, what is the point? Shareholder returns do not come from paper earnings, and LP’s cash conversion cycle ranges from 3 to 4-years. Moreover, returns on capital, though good for an agro biz, are also poor at a long-term ROIC of 5%.

Most importantly, it is also plausible that the bump in revenue and earnings FY21-23 is the result of inflation (even with AVCO accounting): the aging required before a bottle is sold means that pre-inflation wave costs are partly matched to post-inflation wholesale prices, resulting in an artificial, high margin that is not the result of strategic success. See the widening disconnect between COGS and wholesale prices per bottle below. Thus, with a full inventory turn every four years, we should expect margins to normalise in FY27-28, if inflation drops back to a reasonable range.

The third issue is an over-reliance on pricing. The core of champagne is that it is a wine for big celebrations. But past a certain price point, I could see a snap in demand. Volume has, essentially, not grown at all since the late 1990s, whilst the average price has been bumped from €13.6 to €19.4. How sustainable can this be? I would be concerned.

Last but not least, LP is also difficult to place as a business. It is lodged in an awkward middle-ground between a very high-margin, strong brand power, low volume business (gross margins for ultra-premium brands like Salon could exceed 95%) and a high volume, low-margin producer. Equally, though the champagne designation does offer a great deal of protection, it is not as though there is no competition within the space itself: there are literally hundreds of champagne houses, which changes the dynamic significantly.

Overall, then, LP does not seem attractive: there is no margin of safety here.

Disclaimer: this write-up describes the author’s own research and opinions, and does not constitute investment advice, whether explicit or implied. Invest at your own risk and do your own due diligence. I do not hold a material position in the issuer’s securities.

I have just confirmed with LP that they use weighted average cost to calculate COGS. So we should not have a large inflation mismatch. If someone has an idea to why the cost per bottle decreased in 2023 vs. an increase in general inflation, would be highly appreciated.

Insightful, thank you.

Dont they use weighted average cost to calculate COGS (instead of FIFO)? Meaning that the COGS of FY23/24 should already incorporate 3 years of inflation and 1 year of pre inflation. (I dont have gross margins 23/24 yet, but EBIT margins are higher again). I am still puzzled by the decline in unit costs in FY22/23 though.

RoE is quite low indeed. However, incremental RoE might be higher. My reasoning is that their investment in inventories is mainly driven by their premiumization strategy. Premium champagne stays longer in the inventory and hence the need for inventory investment. On the other hand, premium champagne has also higher profit margins, and hence leads to higher return on incremental capital.