Domino's Pizza Group (DOM)

Bungled international expansion, fears of saturation and cannibalisation, but fundamentally excellent...

Investment Case

Very attractive model with defensive characteristics.

Domino’s Pizza Group (DPG) is a strongly branded, digitalised logistics business with captive buyers; contracts with >80% of franchisees require them to buy their supplies from DPG, and it is incentivised to be the most convenient, lowest-cost wholesaler for the others. DPG has shown an excellent long-term system sales CAGR of 14% in the last 25-years and 9% in the last 10-years. Moreover, it boasts very high returns on capital, an EBIT margin of 19%, and a full cash conversion. Though the first priority is volume growth, there is lots of free cash flow left for shareholders: DPG bought back about 10% of its shares in the past year.

With half the UK pizza market under its control and significant economies of scale, DPG allows its franchisees to make the cheapest pizzas and be the value choice for consumers. This contributes to best-in-class store economics, with an average sales level of £1.2m and an EBITDA margin of 13%, plus a payback period of 4-years; competitor stores typically deliver half as much revenue at a lower margin. These economics also strengthen the general defensiveness of the model: system sales grew at double digits through both the financial crisis and COVID.

Good probability of a successful turnaround.

DPG was in the doldrums in recent years due to a failed international expansion, franchisee dispute, and lack of leadership. There are also doubts about its ability to increase store counts in the UK and Ireland and fears of aggregators.

However, DPG has a refreshed board with an incentivised and experienced CEO, Andrew Rennie, who spent three-decades in the Domino’s Pizza universe, starting as a franchisee himself. Rennie is prioritising core growth in the UK and Ireland through a focus on franchisee profitability and logistical efficiencies, digital opportunities, the value proposition of cheap, hot pizza that arrives in 25-minutes, and store expansion in virgin and split territories. He has also explicitly stated that another attempt at international expansion and similar investment programs would require carefully determined guardrails and certainty.

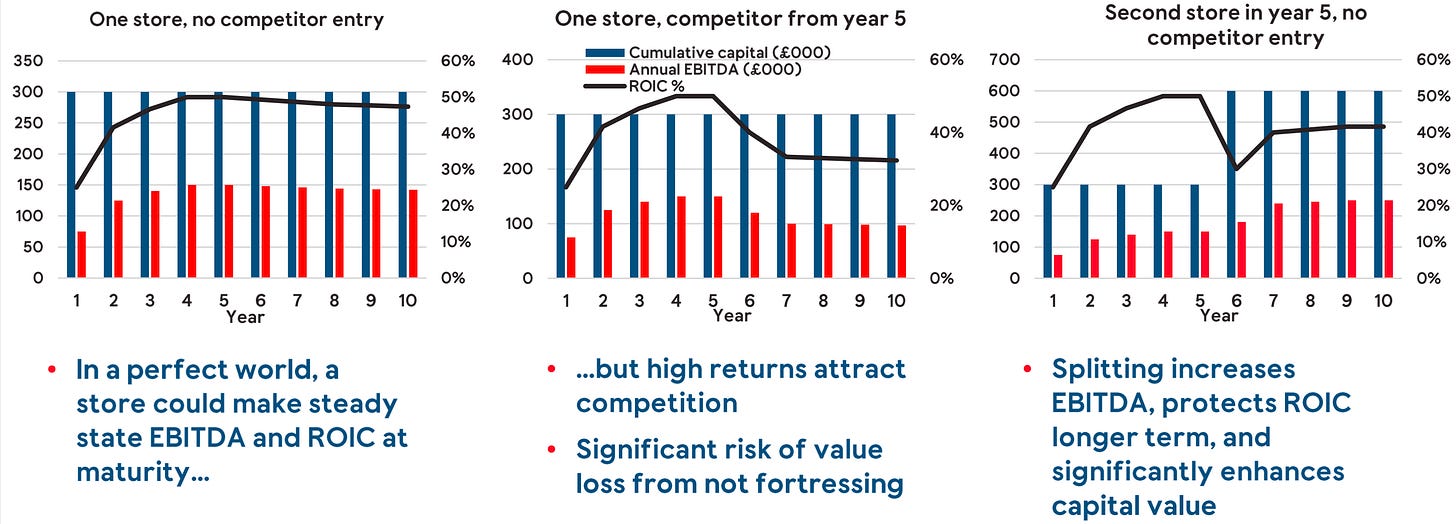

Store count is critical to growth, as DPG depends on volume. Though splits do lead to initial cannibalisation, overall volume and profitability increase due to shorter leg times and more profitable collection orders. DPG is also under-penetrated compared to other master franchisees and quick-service restaurants, and can count on network expertise from the very wide Domino’s Pizza network to ensure success. Case studies of the split strategy have been shown to be very successful, both financially and in terms of excluding competitors from territories. DPG’s best-in-class unit economics also provide chances to expand in smaller address-count zones, with these stores sometimes doing higher sales than the system average.

DPG has listed on aggregators Just Eat and Uber Eats in the past year, and management has found that both current customers order more and that 9/10 customers won are incremental, with solid profitability despite commissions. The reason that DPG still does its own deliveries for aggregator orders is that they know their value proposition: reliable, lowest-price pizza delivered faster than anyone else. The entire network is optimised on these points, and aggregators are unlikely to match or dilute this offering.

Business Description

Domino’s Pizza Group (DPG) is the master franchisee for the Domino’s Pizza brand in the UK and Ireland. As of 1H24, it counted 1,340 franchisee stores in its system, plus 51 corporate or directly-owned stores. DPG has delivered an excellent 15% revenue CAGR in the FY98-23 period at an underlying EBIT margin of 19%, and with very high returns on capital. It also holds half of the UK pizza market, and is multiples the size of the nearest branded pizza competitor.

Pizza is the most popular takeout food, followed by Chinese and Indian, and DPG’s customers typically order four times per year. EY-Parthenon research commissioned by DPG in 2018 showed that brand power is most important for pizza buyers. Moreover, it revealed Domino’s Pizza (DP) was the sole brand with a positive net promoter score of 10%, others being negative; the highest customer satisfaction, at 58% versus 48% and 38% for Just Eat and Pizza Hut, respectively; and the highest brand awareness of 82% versus 71% for Pizza Hut and 39% for Papa John’s.

About 3/4 of DPG’s sales consist of actual pizzas, with the rest being ancillaries like fries, drinks, sandwiches, wraps, etc. DPG sold 112m pizzas in FY23 on 71m of orders; this corresponds to 1.6 pizzas per order excluding ancillaries. 90% of system sales were digital, with 74% of those being through the DP app.

The average delivery time in FY23 was 25-minutes, and 79% of orders were delivered on-time i.e., in <30-minutes; these are industry-leading figures. 36% of orders were collected, and this is a more profitable channel due to the lower labour cost (no driver necessary). There is also a very low, 10-15% overlap between collection and delivery customers.

Most importantly though, 98% of DPG’s sales are through promotions and offers, and it likely exercises decoy pricing: the higher price of standalone pizza orders serves as an expensive anchor that drives consumers to spotlight deals, which flood the menus. Bundles are very common, and their higher price can distract from the fact that DP is the cheapest pizza available.

In the past year, DPG made the decision to list on the popular aggregator platforms Just Eat and Uber Eats, though its own drivers still deliver the product to protect its high-speed value proposition. Interestingly, 9/10 customers won through aggregators are non-core i.e., they would not otherwise have bought DP. This makes their sales contribution incremental, a primary reason that partnerships with aggregators have been made permanent. Extant customers have also been shown to order DP more frequently if it has an aggregator presence.

DPG reports system and group sales. System sales, which stood at £1,541m in FY23, consist of all of the sales in the franchised and corporate store network. DPG’s £667m of group sales are comprised of £471m in food and non-food supplies, £84m of royalties, £33m of own store sales, and £80m of advertisement and online commerce fund contributions.

This suggests DPG is less of a franchisor and more of a branded logistics business with captive buyers. Part of the reason for this lower royalty contribution is that DPG has less bargaining power over franchisees; its largest two accounted for 38% of group sales in FY23. In contrast, other master franchisees and the U.S. business have a hard limit of 10%.

DPG makes all of its own dough in commissaries, which is then distributed to franchisees through a wholly-owned logistics network. The remainder of food and non-food supplies are sourced from third parties. The three most expensive components of DPG’s COGS are cheese, meat, and paper, and franchisee stores receive up to four deliveries per week. Rebates and discounts on supplies are offered if franchisees achieve volume targets or implement promotions.

It is crucial to note that the fates of all stakeholders in a franchise like this are intertwined: DPI succeeds if DPG and other master franchisees succeed, and the latter succeed if their end-franchisees perform. This is a clear win-win, and it sets a natural limit to squeezing counterparts. Agreements between these parties are generally cooperative, friendly, and simple.

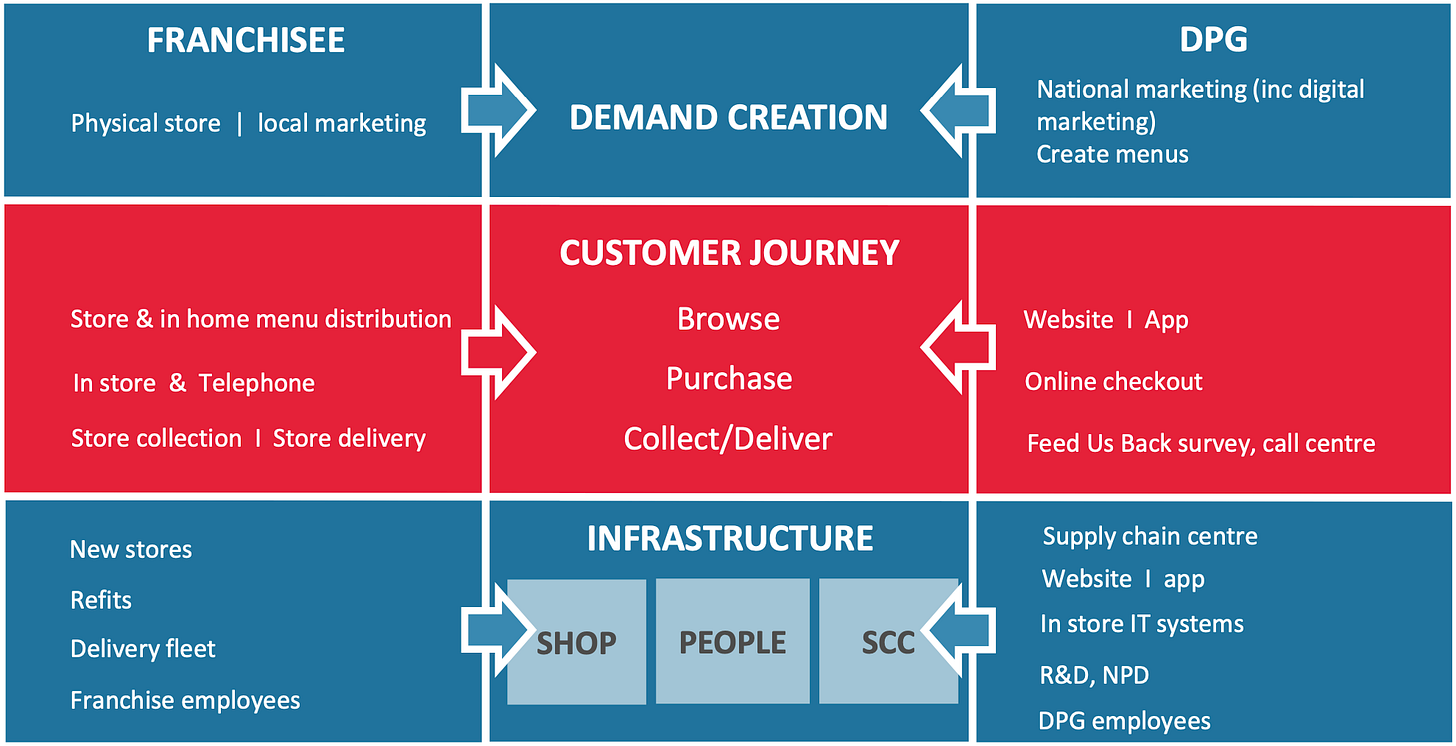

DPG kicks up 2.7% of system sales to Domino’s Pizza Inc. (DPI), which includes a 30 bps discount based on store growth. This agreement is perpetual and renewed regularly with terms of 10-years, provided DPG continues to add stores and execute well. The current agreement demands 1,346 stores by FY26, and DPG will likely surpass that number as soon as FY24, suggesting the growth clause is reasonable. DPI also conducts regular inspections of franchisees to ensure compliance with its brand rules and standards. Surprisingly, DPI’s international operations account for a mere 7% of its total sales, but this is definitely sufficient to guarantee DPI’s interest in fruitful relationships with master franchisees.

DPG’s own 10-year agreements with franchisees stipulate a royalty of 5.5% on their sales, with 20% of any royalty increase passed up to DPI. About 5% of sales go to DPG’s national advertisement fund and 1% flows into its ecommerce fund. Both of these functions benefit the entire network, and DPG is not allowed to retain a fund surplus as profit. More than 80% of agreements with franchisees also prohibit buying from other suppliers, though this seems very unlikely, considering DPG’s economies of scale and obvious incentive to be the lowest-cost provider. Other points are that there are cooperative area development agreements in place, that DPG sets the menu, and like DPI, it also checks its franchisees are aligned with its corporate standards to shield the brand from bad apples.

In general, then, DPG provides its brand, supplies, centralised services, training, and general support in exchange for a royalty on franchisee sales, who run the day-to-day operations. More specifics of responsibilities are shown below.

It might help to draw a comparison between a typical quick-service restaurant and DP’s model to help understand the nature of this business further.

When a restaurant runs well, it benefits from real operating leverage, but with poor revenue, it quickly implodes through a high proportion of fixed costs. Restaurants also make retail margins, have significant capital intensity, and count both price and volume as value drivers. In contrast, the DP model has low capital intensity, is very scalable, and has a high share of variable costs through COGS, distribution, and administration. It also makes a wholesale margin, is far more dependent on volume, has much higher returns on capital, and effectively controls the entire customer experience, end-to-end.

The profit drivers also differ for DPG and its franchisees.

DPG sells supplies to its network at cost-plus wholesale prices, with a persistent goal of being the lowest-cost provider. But because uncontrollable supply-side factors like the weather and FX rates drive market prices, raw volume is the engine of performance for DPG. In contrast, franchisees set their own retail prices and handle local promotions and deals, with pricing influenced by demand-side factors such as competitor activities, consumer confidence, wage growth, etc. For franchisees, then, the typical tradeoff between higher margin/lower volume holds, in the form of retail-minus pricing.

What this disconnect in drivers means, generally, is that pricing freedom for franchisees comes at the cost of margin volatility.

The unit economics of a DPG franchisee store are best-in-class. Upfront costs for a new store in a virgin territory are around £350k, including a £30k one-off fee, equipment, and core supplies. The Homegrown Heroes program specifies that about 20-30% of this sum needs to be available in cash right away. The time until opening is about 12-months, and the typical payback period is 4-years. Average EBITDA in FY23 was £158k for a 13% margin, which has been broadly maintained in recent periods and implies £1.2m in average sales. The normal address count for a DPG franchisee store is 21,000, and capital value is around £1m, with stores being tradable within the network.

For a new store in a split territory i.e., a divided one, the upfront cost is the same, though the payback period increases to 6-years. The “donor” store also temporarily loses up to £200k of EBITDA, which is compensated for by higher overall volume and profitability. With bank financing, the upfront costs for a split store more than halve through a down-payment, and the payback period shortens to 4-years.

At the high-end, franchisee shop costs primarily consist of labour and food (about 30% each). Add to that mileage (4%), the DPG royalty (5.5%), contributions to the national advertisement and ecommerce funds (5% and 1%, respectively), local marketing (4%), occupancy (5%; DPG does a head lease and then leases these back to franchisees at cost), and other expenses (5%), and we are left with a roughly 10.5% EBITDA margin. Of course, the food component is cyclical. Half of the labour component is variable (drivers), and lease and other opex are the primary fixed costs. There is also the flexibility of local pricing and digitalisation to consider, which also drives margin variations.

The failure rate for DPG stores is extremely low, and for DPG’s competitors in the UK and Ireland, upfront costs are similar but typical revenue is halved, with lower proportional profitability. Of course, this makes these competing stores less viable and attractive generally, but it also means that there is less potential for smaller stores in lower address-count areas (further penetration).

In fact, Papa John’s and Pizza Hut, both significant competitors, have been net closers of stores. Papa John’s is in the midst of a UK turnaround and expects profitability in the second half (hundreds of stores, one logistics centre). Excluding disposals of international operations in FY20 and FY21, DPG has been a net opener throughout its entire existence as a firm, and this will most likely continue (see Strategy).

DPG has a very experienced franchisee base; the youngest franchisee has been in the biz for a decade. Franchisee operations are often generational, with networks passed down to children (the DP brand has been around for six decades). Importantly, its franchisees are eager for growth and have strong balance sheets. It is not at all uncommon for franchisees to rise up through the organisation; the best evidence of this is DPG’s current CEO, Andrew Rennie, who also stated that most of Domino’s Pizza Enterprises’ (DPE) CEOs had been former franchisees.

An important question: how does store growth materialise, and what exactly are these “splits”?

DPG and its network expand in two ways: starting stores in virgin territories or splitting settled ones. Though splitting results in cannibalisation and a temporary EBITDA loss for the donor store, absolute sales and profitability do theoretically increase with time. This is because drivers have shorter leg times and can deliver more orders i.e., volume, and stores also benefit from more profitable collection orders through shorter walking distances. It takes about 12-18-months for sales to return to where they were, and DPG offers incentives for splitting of up to £75k. Most importantly, splitting insulates strongly against competitors, creating a “fortress”.

Recent Troubles

If DPG is such a great business, why has it been punished by the market? We can start with two obvious reasons, both of which came to a head right before COVID.

First, DPG under David Wild, who was CEO from 2014 onwards, bungled an international expansion into the Norwegian, Icelandic, Swedish, German, and Swiss markets. This was due to different product demands, higher wages, poor macroeconomics in Iceland, and poor execution. Total losses from discontinued operations in the critical FY18-21 period totalled £139m, and the board resolved to dispose of these operations in Oct 19, which was two months after David Wild caved to the pressure to step down, and one month before DPG’s CFO died in a shock snorkelling accident. The same year, DPG’s franchisees, likely spearheaded by the “big two”, argued for a fairer division of profits.

The international operations excluding Germany were fully disposed of by FY21, and the JV for Germany with Daytona, of which DPG owned a third, was sold for a profit of £41m in FY23.

The franchisees also got their dispute resolution in Dec 21 (note the time lag, which probably created deep market uncertainty). Specifically, DPG committed to a £20m capital investment over three-years to strengthen digital systems; promised more marketing expenditures; decided to upgrade a food rebate system provided franchisees met store opening targets and order volume thresholds; and boosted other incentives for store openings.

In return, franchisees committed to opening 45 stores per year for the next three years; to increasingly participate in new promotional deals for delivery and collections; to prioritise and test new technology rollouts and store formats; and to support improvements to the logistics system. A new Memorandum of Understanding is expected soon, though it looks to be in “good shape”, with 80% of it being unchanged from the prior one.

The share price downturn in FY22 is more difficult to explain. System sales are the lifeblood of the business, and though they fell like-for-like on a statutory basis by 4.2%, they in fact grew by 5.3% if the VAT effects (and splits) are excluded. In brief, COVID saw a reduction of VAT from 20% to 15% in Jul 20, an increase to 12.5% in Oct 21, and a reversion to the full 20% in Apr 22. System sales are reported excluding VAT, which means the sequential increase in VAT drove a decrease in system sales, as the VAT is backed out of the order price including VAT.

Consider a recurring order worth £27 including VAT:

At VAT of 5%, system sales would be 27 / 1.05 = 25.7;

At VAT of 10%, system sales would be 27 / 1.10 = 24.5;

At 20%, the system sales would stand at 22.5, and so forth.

This is clearly a reasonable change to make to the numbers. We also need to consider the firm was effectively leaderless from Wild’s departure until the appointment of Andrew Rennie in Aug 23 (see Management). But it seems the biggest fear is that of saturation and cannibalisation. When companies with a store network mature and split territories, things can go downhill, as seen with Dunkin’ Donuts and SBUX. Aggregator platforms might also be a threat.

Market

We know that DPG has a 7.2% share of the £13.4bn UK takeout market, up from 6.5% in FY20; this space is likely growing at low to mid single-digits.

As to the pizza market itself, DPG holds 47%, which is multiples that of the nearest branded pizza competitor - likely Pizza Hut or Papa John’s. Independent and full-service pizza shops hold another 30%.

Of course, DPG’s share of the aggregator pizza market is far smaller, but this might not be the right way to think about it.

Competitive Advantage

As the largest player, DPG boasts powerful economies of scale. This is partly through its vertical integration in dough production (almost 50m kilos made in FY23), but it also stems from its bargaining power with suppliers and optimised logistics. Scale also manifests in the advertising budget, which could have amounted to £80m in FY23 based on average sales, franchisee store count, and a 5% contribution. These factors allow DPG to offer the lowest possible wholesale prices to franchisees, lowering their unit costs, and thus the end cost of pizza for consumers, helping DPG maintain or win market share from smaller players.

As mentioned, DPG also benefits from best-in-class store economics. Competitor stores typically deliver half the sales of a DP franchisee, and with lower profitability, which means that DP attracts more franchisee interest (broader choice, can select higher-quality operators) and has exclusive opportunities to expand in lower address-count territories. ROICs for stores can exceed 40%, and splits also fortress territories against competitors. When combined with a storied brand that is six-decades old, this is a very strong proposition for a prospective franchisee.

Management

Andrew Rennie was appointed CEO in Aug 23, ending a period of uncertainty in DPG’s leadership.

His background is exceptional. At age 15, Rennie signed up to train for the position of technician in Australia’s Air Force, and after 10-years of service, he left to start a 3,000-address franchisee store in Darwin, Australia; this is half the address count of the smallest DPG store today. Rennie developed that store into Australia’s best within 18-months, before being bought out and made a shareholder of DPE. Next, he worked directly for the DPE master franchisee itself, and shot up the ranks to hold several regional CEO roles for DPE, in France and Belgium, Australia and NZ, and finally Europe. In all, unlike David Wild, Rennie has spent three decades in the Domino’s Pizza system, and his financial track record is very good; he seems like a grinder and has sat at both sides of the franchisor/franchisee table.

From his calls, Rennie has a hardened, general belief about the way forward for DP.

“And the title of my speech [at a DPI event in Vegas in 2018] was “Grow or Die”. The US lawyers didn't want me to have that, but I told them to get stuffed. And I still think it's as relevant today as it was 5 years ago for any business: if you're not growing, you’re dying. So we have to have this growth mentality every day […].”

Growth is very important for DPG, which, as mentioned, thrives on volume instead of price.

Strategy

Formally, DPG’s strategy is four-pronged:

Focus on franchisee profitability and logistics. More digitalisation, efficiencies, and automation would help DPG lower the cost of supplies for its franchisees, increasing their profitability.

Deliver value to customers. Rennie’s definition of Value = (Service + Product) / Price. DPG added a lighter lunch menu in Apr 23, and also plans to drive a higher share of collections (relatively low), and shorten delivery times. New products are also planned.

Accelerate digital. Increasing average order frequency of the 13.5m active customer base to more than 4x per year, in large part through a new loyalty program that could be launched in CY25. This is looking like a “Buy five, get one free” type deal.

Open more stores. These include virgin territories, splits for more penetration, and a particular focus on lower address-count areas (less competition, brand power a significant advantage).

The headline numbers for this strategy are these: £2bn in system sales by FY28 with 1,600 UK and Ireland stores, and £2.5bn by FY33 with 2,000 stores.

Though the UK and Ireland are the definite focus, other opportunities for long-term growth include: adding a second brand, working with corporate stores and JVs, and international expansion. Some of these sound unwise for obvious reasons, but Rennie has stressed a rigorous, careful approach to capital allocation with guardrails.

Speaking of, DPG has a formal capital allocation framework:

Incentives and Ownership

How is Rennie incentivised to make this happen?

Rennie will be paid £775k in FY24. His maximum bonus is 150% of this, based on achieving PBT growth targets (65%) and individual business targets (35%). Two-thirds of this bonus is paid in cash, with the remainder in deferred shares vesting over three-years. Rennie will also receive an LTIP share grant in FY24, also vesting over three-years, based on EPS targets (25.8p in EPS by FY26; 70%) and relative TSR (30%). The latter target is useless considering Rennie has control over fundamentals but not the share price.

Through LTIP options and conditional shares, Rennie theoretically held 3.4m shares as of FY23, vesting over three-years in Aug 26. 3m of these options have a strike price of £5.41, and would then be worth upwards of £16m. Edward Jamieson, CFO, was exposed to 1.3m shares (almost entirely options). Matt Shattock, Chairman, holds 500k shares outright and was paid £482k in FY23.

Abrams Capital Management, led by David Abrams who worked under Seth Klarman at Baupost, holds almost 10%, making it the second-biggest shareholder after Capital Group (14%) and before Browning West (9%). Hence value investors can consider themselves in good company. Browning West is associated with former board member Usman Nabi, who stepped down in Aug 23.

Risks

Saturation/cannibalisation. It is possible that DPG’s strategy of new stores in virgin territories, expansion in smaller-address-count areas, and splits does not produce as much growth as desired. If this is the case, it would squash expectations and suggest that DPG’s potential in its core market has been fully exploited.

Mitigants: DPG can draw on the vast experience of DPI and other master franchisees to optimise expansion and do it correctly. DPG is also less penetrated than other master franchisees, suggesting that if there is a strategic risk here, it is much lower than for its network peers. Average population per store in the UK is 54k, compared to 35k in Australia and NZ, and 29k for another UK quick-service restaurant. Trials of smaller stores have shown that they can, in fact, produce higher sales than the regional average at equal profitability.

Competition from aggregators. The aggregator model is now central to the takeout experience. DP has seen a clear benefit from listing, but there are threats, too. First, DP has less direct access to data on behaviour, which obstructs targeted marketing, trends, insights, etc. Second, seeing DP alongside a wide range of other options could lead to different choices and a lower brand share of mind. Third, there is possible cannibalisation of own direct sales channels. Fourth, the margin is lower due to commissions. Fifth, aggregator customers are less profitable, and last but not least, aggregators might, sooner or later, deliver better than DP can. DP does not claim to have the best pizza, but it delivers quickly and reliably. If aggregators erode this part of DP’s proposition, there will be a serious problem.

Mitigants: 9/10 aggregator customers are incremental (minimal overlap), and even current customers order more through aggregator listings. DPG’s CFO, Edward Jamieson, has served before as the CFO for Just Eat in the UK and Ireland, and is certainly not naïve about the aggregator model. In calls, it has also been emphasised that aggregator customers are still very profitable for DPG. And on the last point, one should note that DPG is extremely optimised for speed from start-to-finish - the leg time is one part of the puzzle. It regularly hands out awards to the fastest pizza makers in the network.

Another bungled international expansion or an expensive, underperforming acquisition. A lot of DPG’s problems in the pre-COVID period were due to a misguided expansion abroad under David Wild. In an attempt to accelerate growth, such mistakes could be made again.

Mitigants: the fact that these mistakes were so recent and that the board has been refreshed completely since, with a more experienced CEO, suggest a repeat is unlikely. Indeed, the CEO’s message is very clear that there will be a cautious approach going forward.

Franchisee disputes. As mentioned, DPG has less bargaining power over its franchisee network than other master franchisees, with two of its franchisees accounting for almost 40% of group sales. This creates potential for another dispute that would disrupt the whole network.

Mitigants: franchise models depend on cooperations, and this means there is a sweet spot, past which neither franchisor/franchisee benefits from squeezes. Besides this, the most recent memorandum of understanding is now at an overlap of >80% with the next one, which is expected in the next year.

Health concerns. Fast food is unhealthy, and about 38% of adults in the UK are overweight, which means there could be some legislative changes that are unfavourable to DPG.

Mitigant: the likelihood of hard-hitting changes is very low, and DPG can reshape its menu to adapt. Customers also order 4x per year, which makes DP a far cry from a staple food.

Valuation

I value DPG based on two scenarios: one where the headline targets are reached (5% CAGR), and one where this growth rate is halved (2.5%). Note that the sales CAGRs in the last 10-years and 5-years were 9% and 6%, respectively, so the guidance for £2bn in system sales by FY28 and £2.5bn by FY33 does not seem aggressive.

Common assumptions include a WACC of 8% (defensive model), 10-year forecast, and a 13x EBITDA exit multiple in FY33. It is also worth noting that the long-term sales CAGR in the FY98-23 period was 13%.

In the target scenario, DPG would be worth around £4.1, for a 39% upside, and £3.3 if half the targeted growth rate is achieved. I also think there is significant potential for multiple expansion to perhaps 16-18x if the market regains confidence in DPG; this would likely demand several subsequent quarters of growth.

This is more of a compounder than a quick multi-bagger, and it strikes me as a careful play on a wonderful business model where the downside is limited. You also have continuing share repurchases to consider.

Disclaimer: this write-up describes the author’s own research and opinions. It does not constitute investment advice, whether explicit or implied. Invest at your own risk and do your own due diligence. I do not have a position in the issuer’s securities.

Interesting write up. I think the sell case largely hinges on the following points: 1/ like-for-like volumes have declined cumulatively by 7% since 2019. 2/ Pricing has driven system sales and is up 26% cumulatively since 2019, so not much room to continue pulling the price lever. 3/ Although the MoU seems in "good shape", the estate is still top heavy with the big 3 controlling c.50% of the estate and most of store growth since 2008 has come from them. They will likely need to purchase stores from these franchisees and refranchise them to promising operators. This will come at a cost and likely more than the 8x EBITDA multiple paid for the Shorecal stores. 4/ The new buybacks announced are pretty small, only c.1.7% of their mkt cap.

I'd recommend reading the Redburn Atlantic initiation report if you can get your hands on it. The analyst is the only sell rating on the street and called the recent share price decline for the above reasons

Largely agree with everything you've said, although I am put off by their balance sheet.