“A man who doesn't know what happens before he is born goes through life living like a child.”

Marcus Tullius Cicero

Debt: The First 5,000 Years was recommended by someone in my LinkedIn network who I have healthy respect for. I’ve always wanted to learn about the history of finance in detail, from inception to present, and haphazardly studying peculiar financial bubbles, so many of which are strewn across our more recent timeline (think Tulip Mania and South Sea), simply didn’t connect the dots for me.

Also, debt has always played a much larger role in finance than equity. Not only has the instrument been around much longer – traces of debt transactions go back to 3500 BC, whereas the first stock corporation was formed in the 1700s – but even today, the global bond market is sized at around $300tn, compared to around $124tn in stock market value. Graeber’s book, therefore, seemed to be worth the sweat and tears to me, and in hindsight, I can happily say that it was.

Barter Is A Myth, Credit Preceded Everything

Economists claim that we started off with barter, moved to coinage, and only then discovered the infinite wonders of credit. Each iteration in this supposedly linear evolution is presented as a logical solution to a common problem.

Whilst barter, the original system, did allow for the exchange of goods and services, it required a double coincidence of wants: I need to have something you want, and you need to have something I want. If there’s no match, there’s no exchange.

It therefore made sense to store things that everybody wanted, making transactions much more flexible and frequent (commodities like dried cod, salt, sugar, etc.). But certain issues remained… what if the goods were perishable? And how could transactions far from home be made practical?

Enter precious metals, which are durable, portable, and divisible into smaller units. As soon as central authorities began to stamp these metals, their different characteristics (weight, purity) were extinguished, and they became the official currencies in specific national economies or trade regions.

Banks and credit followed thereafter, as the final step.

However, Graeber’s main argument is that the above timeline is wrong, as intuitive as it is. Specifically, he posits that we actually started off with credit, then transitioned to coinage, and resort to barter only when an economy or central authority collapses (as with the fall of the Soviet Union). Moreover, he writes that this progression was chaotic and not linear; there were constant rise-and-fall cycles of credit and coinage. It’s obvious that this account is much, much harder to teach at universities, lacking the elegant simplicity of the version that is commonly presented in textbooks.

In fact, to the frustration of economists, it appears there is no historical evidence for a barter system ever having existed at all, except among obscure peoples like the Nambikwara of Brazil and the Gunwinggu of Western Arnhem Land in Australia. And even then, it takes place between strangers of different tribes in what to us are bizarre ceremonies.

“No example of a barter economy, pure and simple, has ever been described, let alone the emergence from it of money; all available ethnography suggests there has never been such a thing.”

However, there is evidence for widespread debt transactions as far back as 3,500 BC in Mesopotamia, which is now modern Iraq. Merchants would use credit to trade, and people would run up tabs at their local alehouses. We know this because Sumerians would often record financial dealings on clay tablets called bullae in cuneiform (successful translation of this language kicked off in the 1800s), which were dug up by archaeologists.

And whilst Sumeria did have a currency (the silver shekel), it was almost never used in transactions. Instead, it was a simple unit of account for bureaucrats. 1 shekel was divided into 60 minas, each of which was equal to 1 bushel of barley on the principle that temple labourers worked 30 days a month and received 2 rations of barley each day. Though debts were often recorded in shekels, they could be paid off in any other form, such as barley, livestock, and furniture. Since Sumeria is the earliest society about which we know anything, this discovery alone should have resulted in a revision of the history of money. It obviously didn’t.

Debt As The Fabric Of Human Societies

Graeber presented perhaps a dozen or so fascinating anthropological case studies in his book. Some of these were definitely too abstract to handle. Among the best illustrations, though, is that of the Tiv people in Nigeria. When the American anthropologist Laura Bohanan went to visit this folk to study their reactions to Shakespeare’s Hamlet, she was immediately given small gifts by her new neighbours upon arrival (1 chicken, 5 tomatoes, etc.).

It was later explained to her, after the initial confusion, that the gifts had to be reciprocated, and that she should give something back which was worth either slightly more or slightly less, but never the exact same. The reason is simple: receiving a chicken and giving one back would settle the transaction and provide no incentive for further interaction of the kind that is crucial in a small, rural, collectivist society. You could say that this constant exchange was the very foundation of Tiv society, and perhaps all others; if everyone is in debt to each other all the time, no one can retire from the community.

The passage reminded me how fundamental human reciprocity is, even in our individualistic, overpopulated societies, and that it can’t be explained by economists because it’s theoretically irrational. It’s a simple give-and-take, and both parties win. Buy a friend a beer, and he’ll buy you the next one; produce good work for your boss, and he’ll vouch for you; remember someone’s birthday, and he will remember yours. But there’s no cold-blooded calculation of who owes what to whom at the end of the quarter.

Freeloaders, when identified, are shunned, which serves as an extremely strong deterrent. Consider also how uncomfortable you feel when you receive a gift or favour from someone, but you’re not sure who. I mean, it causes actual distress. There is but a single difference between a social IOU and debt - the latter can be precisely quantified. No wonder that this financial instrument was the first on the scene.

Religion, Language, And The Conflation of Debt With Morality

Religion serves as the bedrock of modern moral principles, and the main texts spill over with the language of debt. Below is perhaps the most famous quote.

“Forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors”.

Lord’s Prayer, New Testament, Matthew 6:12

And here’s another.

“The wicked borrows and does not pay back, but the righteous is gracious and gives.”

Book of Psalms, 37:21

In accordance with the rule of reciprocity, then, defaulting on debt is a negative thing that should be looked down upon. But with the advent of capitalism, this attitude has certainly changed. Think about it… the system provides safety from debtors’ claims through structures like the limited liability company. This signals society’s positive regard for entrepreneurship; it often takes a second or third attempt to succeed.

But as most people know, what is infinitely worse than borrowing and defaulting is lending with interest i.e., usury.

“And if you lend to those from whom you expect repayment, what credit is that to you? Even sinners lend to sinners, expecting to be repaid in full. But love your enemies, do good to them, and lend to them without expecting to get anything back.”

Luke, 6:34-5

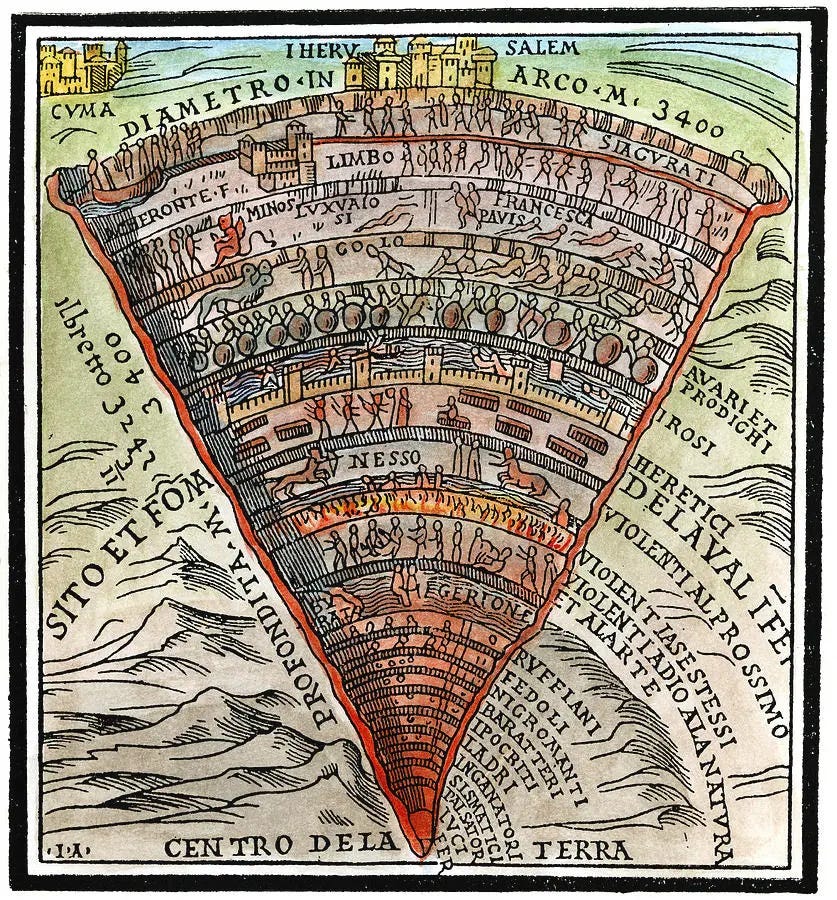

In Dante’s Inferno, which is the first part of Dante Alighieri’s poem Divine Comedy, written in the 1300s, usurers were assigned to the seventh circle of hell, together with the murderers. Supposedly, this is because usury is making money from money; it’s not an art, hence it conflicts with God’s design for the world. Now that’s a bad omen for some financial professionals.

What about, say, Islam? It’s all quite fascinating. Usury in Islam is referred to as riba, and speculation is described as maisir. Both are explicitly forbidden in the Koran, the former because money is thought of as a simple medium of exchange with no inherent value. The Mekkan verse was the first to be revealed on the topic of usury.

“And what you give in usury, that it may increase upon the people's wealth, increases not with God.”

Koran, 30:39

Obviously, inflation and the time value of money also apply in the Middle East, so modern Islamic banks have found workarounds like equity participation systems. In the case of a corporate loan, for example, the lending bank will take a share of the profit as interest at maturity, together with its initial principal. This is called mudarabah, where one party brings capital and the other effort. Further workarounds exist.

Besides religious passages, the language of debt also permeates daily life.

“The French merci is even more graphic: it derives from ‘mercy’, as in begging for mercy; by saying that you are symbolically placing yourself in your benefactor’s power - since a debtor is, after all, a criminal.”

“Saying ‘you’re welcome’ or ‘it’s nothing’ (French de rien, Spanish de nada) (…) is a way of reassuring the one to whom one has passed the salt that you are not actually inscribing a debit in your imaginary moral account book. So is ‘my pleasure’ - you are saying, ‘No, actually, it’s a credit not a debit - you did me a favour because in asking me to pass the salt, you gave me the opportunity to do something I found rewarding in itself”.

Credit Today, Coinage Tomorrow, And So Forth…

As stated, Graeber wrote that history is marked by flip-flop cycles of credit and coinage. But the question is, why? Likely because of cycles of war and peace.

“While credit systems tend to dominate in periods of relative social peace, or across networks of trust (…), in periods characterised by widespread war and plunder, they tend to be replaced by precious metal”.

The reason for this is twofold. Unlike credit, gold and silver can be stolen through plunder, and in transactions, it demands no trust, except in the characteristics of the precious metal itself. And soldiers, who are often constantly travelling with a fair probability of death, are the definition of an extremely bad credit risk. Who would lend to them? Armies typically created entire marketplaces around themselves.

“For much of human history, then, an ingot of gold or silver, stamped or not, has served the same role as the contemporary drug dealer’s suitcase of unmarked bills: an object without a history, valuable because one knows it will be accepted in exchange for other goods just about anywhere, no questions asked.”

Fixing The Financial System

Graeber was a radical thinker, and an excellent one at that. He recognised that the current system favoured the rich, and that it was clearly unsustainable.

Fiat money, with its value being nothing more than psychological, is like a helium balloon. And in all our wisdom, we have intentionally let go of it (Nixon abandoned the gold standard to finance the Vietnam war), letting it rise higher and higher, with no limit in sight.

Economies are fuelled by giant debt bubbles, and around 95% of money in Western Europe and the U.S. is digital credit, with the miniature remainder being physical cash (which is also, theoretically, credit).

Financial imperialism is real. For example, the US finances its perpetual budget deficit through its network of allies (Japan, the UK, Korea), who buy its debt securities. Inflation erodes the principal over time, the interest is pitiful, and the debt is rolled over indefinitely. Just look at the regular farce of US debt ceiling discussions. So are these loans or tribute payments? And it runs much deeper than this.

Instead of central banks, it is commercial banks that create almost all money, marking up accounts and inventing the corresponding deposit liabilities, whilst earning real interest at our expense.

Inflation wouldn’t be a problem if credit was invested into productive endeavours. Instead, it’s used for unproductive means, like bidding up the value of financial assets.

Banks are the economy, which means that bailing them out would pull the rug out from under us.

“We cling to what exists because we can no longer imagine an alternative that wouldn’t be even worse.”

What Graeber wanted to see was the following.

A comprehensive democratisation and decentralisation of finance.

A focus on productive ventures, instead of playing with intangible money.

A universal basic income and provision of basic services to all.

And above all…

“we are long overdue for some kind of Biblical-style jubilee: one that would affect both international debt and consumer debt. It would be salutary not just because it would relieve so much genuine human suffering, but also because it would be our way of reminding ourselves that money is not ineffable, that paying one’s debts is not the essence of morality, that all these things are human arrangements and that if democracy is to mean anything, it is the ability to all agree to arrange things in a different way.”

Graeber certainly tried to push us in the right direction, having been a key member of the post-GFC Occupy Movement in its early days. But it would take a massive crisis to change the current system.

P.s. David Graeber unfortunately passed in 2020. If you want to learn more about him and his ideas, I obviously recommend this book, his talk at Google, and the fantastic documentary 97% Owned, which reflects much of Graeber’s own thoughts. While I would have liked to present a concise and digestible timeline of Graeber’s theory of money in a final section, the topic is much too complex and long to present in a blog format, without omitting at least some of the most important parts.

Great article dude!